My First Lessons in Business Came From Gaming

By Hauk Nelson

Like many unable to leave their homes, I’ve turned to gaming more in my free time. If we’re being honest, I was doing that anyway. One of the games I’ve been playing has been Animal Crossing: New Horizons. For the unfamiliar, New Horizons places you on a deserted island, with the task of building it into a functioning society. Players fish, catch bugs, and go into massive debt to turn their islands into a tropical paradise.

The appeal of Animal Crossing has always been the ability for players to customize everything. From their homes and clothes to the design of their towns, New Horizons has been an escape for many looking to take edge off of the current climate. Though decidedly not an esport, esports organizations have even gotten in on the fun, creating digital versions of their apparel for fans to wear in Animal Crossing. Unsurprisingly, 100 Thieves does the best job - my fandom of them as a company is well documented.

One of my favorite parts of the game is turnips. Every Sunday, Daisy Mae visits your island to sell you turnips. Fans of the series will recognize her as the granddaughter of Joan, a sow that also sold turnips. Daisy Mae has taken over her grandmother’s business, known as the Sow Joan’s Stalk Market.

At face value, turnips are not valuable. They cannot be stored, and don’t give any special power ups. However, they can be sold for a profit. Throughout the week, the turnips you purchased can be sold to Tommy and Timmy, the local proprietors on your island. Turnip prices change every twelve hours, giving players a chance to sell back the turnips they bought. The turnips you buy go bad each Sunday, pushing you to sell at the right time.

Children across the world are becoming commodity traders, and they don’t even know it. Communities are forming to share prices on their respective islands. Guides are being created to demonstrate how to best time the market, and when we may expect peaks and dips. The youth of today are learning how to arbitrage. If only there were a New Horizons futures market.

My First Business

This made me realize that my first lessons in business also came from gaming, mainly through RuneScape. RuneScape is an MMORPG similar to World of Warcraft. Players level up, both in combat abilities, but also in skills that generate income, such as fishing. Many players aim to max out these stats, getting them to level 99. Wealthy players would spend large sums of gold simply to shave off time and hit this goal more quickly.

In RuneScape, one of the most common ways to earn experience quickly was to harvest flax and turn it into bowstrings. These bowstrings could then be turned into bows. Simultaneously, players could level up in crafting and fletching - but who has the time to harvest all of that flax? I did.

Harvesting flax was boring and time consuming. It was often sold in quantities of 1000, making the process aggressively tedious. I persevered through hours of right clicking and harvested 2000 flax. I then found my first buyer - Cheeseyc0ad. I sold my 2000 flax to him for 320,000 gold pieces, or simply 320k. Thrilled to make a sale, I asked if he would buy more, and he would. The only problem being that I didn’t want to harvest all of that flax again. I’m a busy man with gold in my pocket. I have quests to accomplish and beasts to slay.

I had to find someone even more novice than myself to harvest the flax for me. I quickly found that in iowaf00tball1997, who I paid 120k for each 1000 flax. I would in turn sell the flax to Cheeseyc0ad for 160k, making a profit of 40k for five minutes of communication. Mythmaster22 (me, don’t ask) had quickly amassed a fortune, with multiple flax runners and a few buyers. Ten year old me even kept a journal of my transactions, suppliers and customers. Pearls of wisdom included “Cheesec0ad: Good, don’t lose him. Islandmonkey437: Don’t care if lose him.” Mythmaster22 was too busy becoming a flax mogul to take detailed notes.

Life Lessons Learned the Hard Way

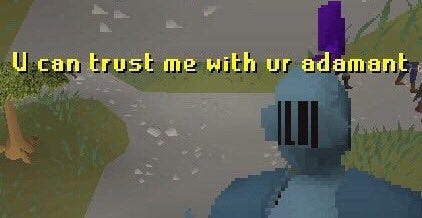

Although there were positive lessons from my RuneScape experience, I also learned from mistakes. This may come as a surprise to you, but sometimes people lie on the internet. Especially in a game where there are no consequences, and the victims are unsuspecting children.

Now a master of arbitrage, one day I find myself in a bank. Banks were often a hotspot of trading, and in one corner I see a player searching for an item, offering 800k for it. This item was worth substantially less, but some players would overpay if it meant getting an item quickly. In the other corner was a player offering that item for 600k. Mythmaster22, a master of business and opportunity, acted quickly to buy the item for 600k. However, as soon as I made my way to the other corner, the player was no longer interested in the item for any price, let alone 800k.

I’d been scammed. I now had an item worth 400k, and had spent 600k on it. Those two leave the bank with more gold in their pockets, and I’m left floored that I fell for the trick, though perhaps now a little wiser. I sign off for the day, less of a master than I thought I was.

Scams are common in RuneScape. A common one that I’d fallen for before was known as armor trimming. Certain armor was trimmed with gold, providing no combat bonuses but plenty of “looking cool to all your friends” bonuses. Having seen this cool looking armor before, I was delighted when someone approached me and told me they could trim my armor for me. All I had to do was give it to them. Simple enough, right?

What a fool I was. I handed them my armor and they ran off. You can walk or run in RuneScape, and this guy bolted immediately after our trade went through. I tried messaging him, following him, and reporting him, though nothing happened. It turns out, you can only buy trimmed armor, people can’t make it for you. Once again, I resigned myself for the day. Though admittedly, I did try the same trick on other people later. I’m sure there’s a lesson in that somewhere.

Resource Management

Games such as Age of Empires, Age of Mythology and Civilization teach players to manage resources while competing against others. Players use their initial resources, often a plot of land and a worker, to build a sprawling empire. As ruler, I decided which resources villagers would work towards, and what to spend these resources on. Should I spend this gold to bolster my military and gain more territory? Or should I double down and increase the number of villagers, so I can gather even more resources?

Because I use my time wisely, I also got into tabletop gaming. Ironically, though I prided myself on my resource management skills within games, I can’t think of a bigger timesink than Warhammer. Along with being absurdly expensive, players can buy, build, paint and then battle with figurines. If you couldn’t guess, I was extremely cool.

In Warhammer, all models have an assigned point value based on their stats. To make competition balanced, battles were set with predetermined points. My 2,000 points worth of models against yours. Warhammer is a balancing act between high value models and the lower value units that support them. Sure, your Vampire Count on Zombie Dragon (I know, this is a bit much) might output a lot of damage, but if it falls, you have no other valuable units left. One cannot put too many eggs in one basket, as a stray artillery shot can wipe out your entire strategy.

The army I played, Orcs and Goblins, was the opposite. Cheap in point value, I could easily outnumber my opponents two to one. However, they were prone to infighting, known in-game as Animosity. Each turn, I have to roll dice for each of my units. On a roll of one, they can’t move that turn. On a six, they charged forward ready to fight, regardless of whether I wanted that or not. For me, Warhammer became a game of reducing Animosity, and reacting accordingly when I failed. I prepared for the worst, and made the best of it when it came. Oh, and I spent hundreds of dollars on plastic. My retirement fund:

Gaming Economics

Some games are so advanced to the point of needing economists to manage their digital economies. EVE Online, an MMORPG set in space, has an extremely realistic economy, to the point of having actual recessions. Nearly all objects in the game are player made. This entails raw materials being mined, facilitated by logistics, processed and produced, and then ultimately sold on the open market.

Territory is claimed by factions of players, though these factions are more in depth than clans we see in other games. These groups have leaders, militaries and will even go to war with one another over territory and resource disputes. New players must quickly join a group for any chance of survival. If they pay their dues, over time they can rise up the ranks in the faction, getting access to more resources and having more authority.

As YouTuber Economics Explained points out, you can actually calculate the GDP within EVE Online. The developer, CCP Games, puts out a monthly report on the values of resources. With multiple charts, metrics outline how much in value has been mined, created and destroyed. Though I never played EVE Online (too busy painting Orcs,) the game simulates a real economy.

Conclusion

All of this is to say that I’ve learned a lot about both business and the real world from games, as counterintuitive as that sounds. From my first lessons in arbitrage and scams, I learned how to see opportunities, as well as to distrust things that seemed too good to be true. Gaming has become a path to not only life lessons, but also a career. The worlds of gaming and esports are full of entrepreneurs building companies in entertainment, art and fashion, and it’s only the beginning. Animal Crossing: New Horizons may spawn another generation of entrepreneurs and creators through the simple selling of turnips.

Hauk Nelson is a Chicago based esports professional currently working at KemperLesnik. These views are strictly his own and not those of his employer. You can read more of his writing at his website, hauknelson.com, and find him on Twitter and LinkedIn.