How to Put More “Character” Into Your NPCs

Geoffrey Golden explores narrative design and imbuing NPCs with life and personality

Want to stay up to date on the games industry? We release a weekly newsletter featuring exclusive long-form content, including the best headlines, releases, and articles in gaming.

There’s something about the term “NPC” (Non-Player Character) that sounds hollow to me. Maybe it’s the ambiguousness of acronyms, or how the term literally sounds like “empty.” As a narrative designer, my philosophy is to think of NPCs less like assets on a spreadsheet, and more like my cast. There are big and small parts, but I believe designers can give any character soul. (Even a character whose soul was stolen by an evil wizard of some sort!) A bit more effort can make a minor NPC more human, and a game’s world more alive.

Rabbit Girl, an NPC from Undertale

When I think of NPCs, what immediately comes to mind are the villagers who populate roleplaying game towns. You enter the village and stop the first wandering stranger you meet, who says something like:

Villager: Do you think the red dragon will come back?

Villager: I hear there’s a mirror in the Fire Mountains that can block its flames.

I’ve seen dialogue like this in countless games, both old and new. I call it “skeleton talk.” On the plus side, skeleton talk is usually efficient. From a gameplay perspective, the purpose of this dialogue is to communicate an important plot point (the town was attacked by a dragon), and guide the player’s next action (go to the Fire Mountains to find a magical mirror).

But as a player and a storyteller, I find skeleton talk unsatisfying. Yes, it tells me what I need to do, but this character is forgettable, and therefore a missed opportunity. Isn’t the point of a story-driven game to immerse you in a fantasy? Forgettable characters like the villager above won’t add to your world. In fact, if the dialogue reads too much like simply a game clue, the NPCs might detract from it.,. It could take players out of the immersion.

After understanding what the requirements for an NPC are from a game design perspective, here are questions I ask myself when writing their dialogue:

Who is this person?

What is their relationship to the player?

What do they want?

How are they feeling?

These are my Four Questions of Personification (patent pending). They allow me to put flesh, organs, all the cool human-stuff onto the skeleton. Let me break each of these questions down, and I’ll show you how answering them leads to richer dialogue.

Zelda’s Old Man

WHO IS THIS PERSON?

Adjectives, adjectives, adjectives. When I start writing a character, I begin by thinking of words that describe a character’s personality. Boisterous, stingy, scared, suave. For minor characters, maybe only one adjective is necessary, but for more important NPCs I’ll come up with several.

Let’s go back to our villager. Say she’s wearing a dirty dress and is carrying a heavy looking burlap sack. What kind of adjectives might describe her personality? Maybe she’s haggard from overwork, or assertive about her responsibilities, or eager to do her part for the village. I’ll say she’s brave, and won’t let some dragon intimidate her.

So, knowing she’s brave, let’s rewrite her dialogue to show that personality.

Villager: That ugly red dragon better not show its face around here again.

Villager: I hear there’s a mirror in the Fire Mountains that can block its flames.

Villager: If I wasn’t so busy hauling grain, I’d get it myself!

Notice we’re not changing the information the player receives. We’re just adding personality. Because we know she’s a brave villager, we can write her as such. She’s not afraid to insult a scary creature. And she’d even be willing to climb the Fire Mountains, which sounds like a pretty dangerous place to climb!

We could also go the complete opposite route. Let’s say instead of brave, this villager is klutzy…

Villager: Oh no! I spilled another grain sack. My lord is going to KILL me.

Villager: Thinking about the red dragon coming back keeps distracting me.

Villager: I hear there’s a mirror in the Fire Mountains that can block its flames.

Villager: I got rid of all my mirrors. I keep breaking them!

For major characters in a game, I like to write them full biographies, so I get a sense of their background and point of view, all of which contribute to scenes. But all my biographies begin with personality trait adjectives, because they help me quickly get my bearings with a character.

Bob from Secret of Monkey Island

WHAT IS THEIR RELATIONSHIP TO THE PLAYER?

Most people have different ways of speaking to their partner, their boss, their pet, and to strangers. I rarely call a perfect stranger “my perfect widdle fuzzball,” and I don’t ask for a Skype meeting with my partner to give “constructive feedback on meal scheduling.” Who the player is to the NPC can make a big difference in how they talk to you. Defining that relationship will bring more personality to your dialogue.

For example, the villager and the player character might be literally related. If the villager is the player’s mother, they might be worried about you, and call you by pet names…

Villager: You don’t think the red dragon will come back... right, dear?

Villager: I hear there’s a mirror in the Fire Mountains that can block its flames.

Villager: But don’t go. It’s too dangerous for my precious angel!

If the villager is a stranger: How do villagers in this town feel about strangers? Are they overjoyed to meet anyone who can help? Are they eager to vent their feelings to anyone who will listen? Let’s say after the attack, the townspeople became paranoid of strangers...

Villager: Who are you? I’ve never seen you before in my life.

Villager: Are you a spy for the red dragon? Hmm?

Villager: Prove you’re on our side. Get us a weapon to fight the dragon.

Villager: I hear there’s a mirror in the Fire Mountains that can block its flames.

By clearly defining the relationship for yourself, you can then communicate it to your players.

WHAT DO THEY WANT?

This is a bit of advice I got from a talented screenwriter named Todd Alcott. He always asks, “What does the protagonist want?” The hero of a story has a strong inner desire that inspires them to action. Tom Nook wants to be a successful businessman. Lara Croft seeks adventure by uncovering lost artifacts. The journey and actions these characters take spring from their main desires.

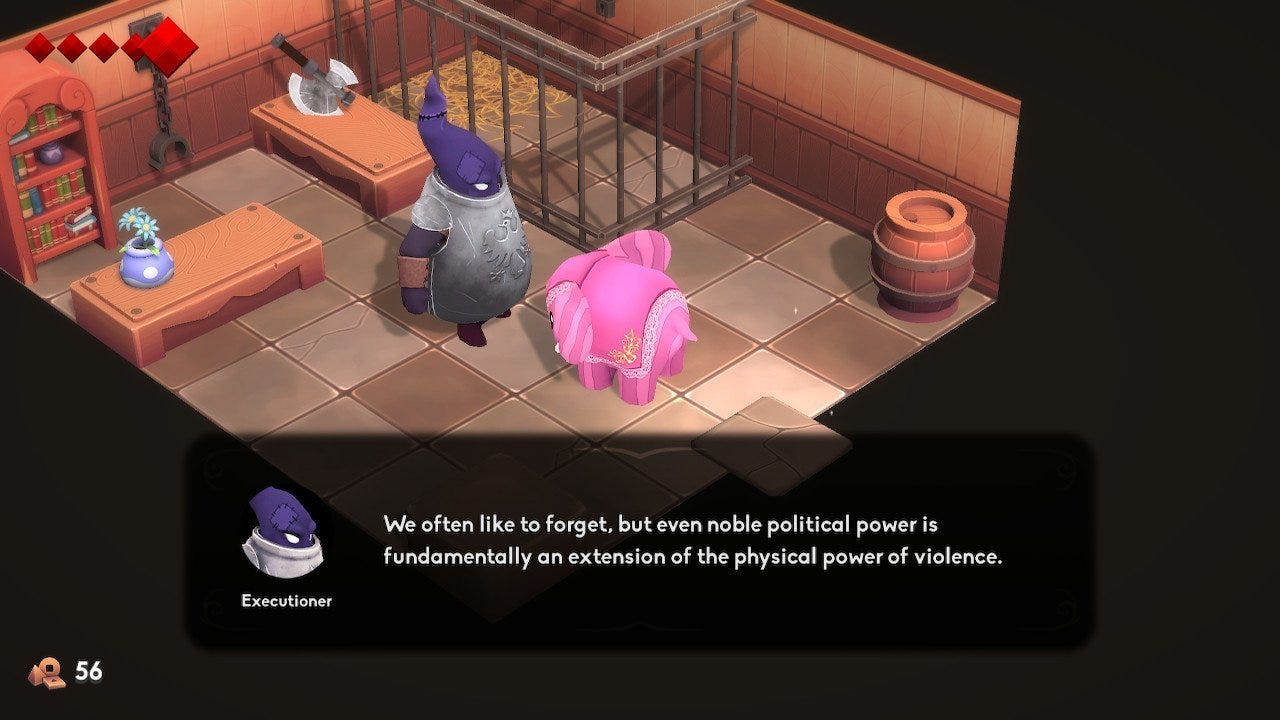

Executioner from Yono and The Celestial Elephants

Minor characters have wants, too. Knowing an NPC’s needs, and stating them clearly, can inspire helpful players to want to assist them. For example, let’s say our villager desperately needs sleep, which she hasn’t gotten since the dragon attack. In this version, I’ll have her state what she wants directly to the player.

Villager: I’m exhausted. Haven’t slept a wink since the red dragon attack.

Villager: This town used to be so peaceful. Now I hear shrieks of terror all night.

Villager: There might be a mirror in the Fire Mountains that can block dragon flames.

Villager: Please defeat the dragon, warrior. I’m so tired...

But she might want something completely different. Maybe this villager is more militant and wants to see the dragon destroyed.

Villager: Finally, there’s a true warrior in town. Have I got a quest for you!

Villager: A red dragon’s been plaguing us. I’d love to see you bash his disgusting head in.

Villager: I hear there’s a mirror in the Fire Mountains that can block his flames…

The villager’s motivation, clearly stated, gives the player a stronger sense for why they’re going on this quest – from a human perspective. It’s not just that you need to go to a location to acquire an item. You’re playing to help a villager sleep, or to satisfy their weird bloodlust! The NPC’s appreciation when the player returns to the village will be an extra reward for a successful quest. What’s at stake for these people, both collectively and individually?

HOW ARE THEY FEELING?

If you stop someone fleeing a rampaging bear and ask them for directions, they probably won’t express much of their personality to you. But you’ll likely get a sense for how they’re feeling at that moment – as they scream in terror – and that’ll make your interaction with them feel very human. After all, what could be more human than our gooey, squishy feelings?

So let’s put our villager in immediate danger. Say the dragon is looming on the horizon…

Villager: What are you doing? RUN FOR YOUR LIFE!

Villager: The red dragon is coming to kill us all!

Villager: Finding that legendary mirror in Fire Mountain might be our only hope!

Villager: It can block the flames and– OH GOD, I can see the dragon’s shadow!

It’s logical that someone in immediate danger might feel panicked or scared, but it’s not always the case. People don’t always feel the same thing in the same way. Let’s say the villager is serene, because her religion provides her comfort…

Villager: The red dragon will not harm me. The goddess sent you here to defeat it.

Villager: There is a mirror in the Fire Mountains. It will protect you against dragonfire.

Villager: The goddess protects me, always.

In a town full of frightened and panicking NPCs, a few expressing very different feelings would stand out and be memorable to the player.

I don’t always answer all four questions for every minor character I write. Sometimes it’s enough to answer one or two. However, I always try and give an NPC justice by taking the time to understand who they are. Just in the same way an artist considers an NPCs facial features, clothes, and how they walk, I think about what they’re thinking and feeling.

Notice that all my examples stayed within 3-4 lines. You don’t have to write a lot of dialogue to give a minor character personality. As the dialogue writer, you just need to make a few decisions and write to them. Who is this NPC? What do they think of the player? What do they want? How are they feeling? Short answers to those questions can go a long way toward bringing your non-player characters — and by extension, your game’s world — to life.

Geoffrey Golden is a narrative designer who has written for Ubisoft, Square Enix, Capcom, and indie studios around the world. He’s the game master for Adventure Snack, a free “choose your path” adventure game played via email.

The editor asked Geoffrey to list all the different platforms he’s written games for. Here goes: Nintendo Switch, Playstation 4, iOS, Android, tabletop RPG (in books, zines, and magazines), Kik Mobile, Facebook Messenger, Adobe Flash, email, and toy robot.

"In a town full of frightened and panicking NPCs, a few expressing very different feelings would stand out and be memorable to the player." -- wise words -- thanks for this, using it for research ;)